[Click on articles/photos for full view in separate tab]

It was a cloudy Saturday, April 27, 1918. A light spring rain was falling when the phone rang in the Milligan household on South Lake Street Road in Pavilion. The news that Mrs. Milligan received when she took the call still echoes with sadness today, 100 years later.

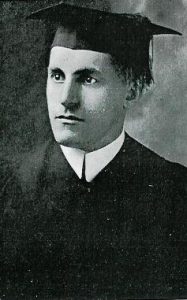

Doctor John Deming Arnett, the town’s popular young physician, had been killed in action “over there” in France. He was Genesee County’s first World War combat casualty.

“His untimely death has moved the community to grief over his early demise and sympathy for his young wife.”

The call came from the brother of Dr. Arnett’s 25-year-old wife, Florence, who was living with her parents in Albion while her husband was overseas. She had received the telegram from the War Department that morning. “Deeply regret to inform you,” it began.

The couple had been married barely more than a year.

It was a tragic ending to what had been a storybook start promising a bright future.

In 1916, Dr. Arnett, a bachelor from Medina who’d graduated from Albany Medical College in 1914 and recently completed his internship at the Hospital of the Good Shepherd in Syracuse, moved to the peaceful small town of Pavilion to set up a practice.

At first, he stayed with and took patients in the Milligans’ home. Later, he rented an office and quarters above the bank building in town, where he brought his new bride after they married in January, 1917.

In ordinary times the story probably would’ve continued as promised; the doctor and his wife building a comfortable and happy life together in the village, perhaps raising a family, the years turning to decades, the decades to lives fulfilled as good neighbors and valued members of the community.

But the times were hardly ordinary. Three months after John and Florence’s wedding day, the United States declared war on Germany. Europe was self-destructing. Britain and France were reeling from bloody losses.

But the times were hardly ordinary. Three months after John and Florence’s wedding day, the United States declared war on Germany. Europe was self-destructing. Britain and France were reeling from bloody losses.

It would take months for America to equip and send an Army. But the Allies had another pressing need that could be filled sooner: trained doctors.

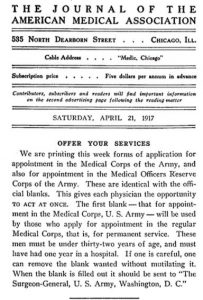

The call went out. Applications appeared in The Journal of the American Medical Association. “OFFER YOUR SERVICES,” an editorial read. “This gives each physician the opportunity TO ACT AT ONCE.”

The doctor from Pavilion submitted his application, and on August 2 he was called into active service in Washington, DC. On September 18, 1917, the newly minted Lieutenant John D Arnett, Army Medical Officers Reserve Corps, left the United States for war-ravaged Europe aboard SS St. Paul.

Arriving in England, the doctor spent that fall working in Royal Army Medical Corps hospitals, primarily the 5th Southern General Hospital in coastal Portsmouth.

At the city’s busy port, hospital ships from France unloaded thousands of maimed and gassed soldiers who’d managed to survive the battlefield and the grueling chain of field medics, dressing stations, burn and gas centers, casualty clearing stations, and painful transport over rough roads in wagons or lorries filled with groaning and dying comrades to reach—at last—home ground and—perhaps, with the help of men like Dr. Arnett—a chance for recovery.

It was here that Dr. Arnett gained first-hand experience in treating the ghastly wounds of war. He would soon need it.

At the turn of 1918, Dr. Arnett was sent to France, arriving there on January 6—his first wedding anniversary. He was assigned to the 99th Field Ambulance, a mobile medical unit in the British Expeditionary Forces’ 33rd Division. The unit’s main dressing station at the time was just west of the city of Ypres, Belgium—or what was left of it.

Ypres was at the core of a bulge in the British line, enveloped on three sides by enemy troops. British and German forces had been slugging it out since July in the infamously bloody Battle of Passchendaele, a town just northeast of Ypres that British forces had finally taken in November but were only barely holding. The conflict is also known as the Third Battle of Ypres, for the city had been the center of two previous major battles for control, and near-constant combat since 1914. Estimates of the total casualties on all sides during the three battles range from 800,000 to one million soldiers.

The landscape for miles was nothing but watery shell holes, debris, and desolation. The cold, wet terrain, churned by daily artillery bombardments, was a sea of mud 15 feet deep or more. The few roads stood like shallow dams barely above the mire. Soldiers walking perilous duckboard trails could slip and be sucked into the muck to their deaths.

Almost immediately, Dr. Arnett was put in charge of patients at a gas and wound station in the ruins of Ypres’ former prison.

Days later, he was assigned to an advanced dressing station even nearer the front lines, where he and his station’s stretcher bearers worked ceaselessly, often under fire, to retrieve and treat wounded troops.

It was the first of what over the next three months would be many rotations for the physician between gas and disease treatment centers, advanced dressing stations, and combat-line infantry stations.

In the midst of all this, possibly as a way to anchor his sanity, Dr. Arnett managed to write many letters home, corresponding with friends and family and former patients in Pavilion. On January 26, 1918, he wrote to his mother:

“I have just come from the line where I have put in my second trip in 8 days . . . . I got along fine up the line and was a much braver man than I thought I was.”

The doctor continued, “They threw over a lot of gas shells during the night but I had a man on guard to awake us if any gas came near. I got so I could sleep with big 8 inch guns bellowing all night within a few yards of me.”

He described one of the horrors of war, using an ironic opening line to soften the image for his mother at home in Knowlesville:

“I have seen some wonderful sights lately. I drained a shell hole and found five bodies partially uncovered just their heads and shoulders protruding into a shell hole. We gave them a reburial and put a cross up.”

On March 29, 1918, German forces launched a massive spring offensive across the Western Front. In Flanders, the German Fourth and Sixth Armies attacked from south of Ypres, and were pushing north and west, attempting to take the hills below Ypres, then the city itself. Their goal was to drive the British and French in southwest Belgium and northern France toward the English Channel.

The 33rd Division was rushed south to reinforce embattled English troops, who were taking heavy casualties and falling back all along the line. Throughout early April the 99th Field Ambulance moved with the struggling infantry, setting up dressing stations behind the lines as needed to treat casualties as the Germans continued to push ahead.

On April 13, the 99th established its main dressing station at an army camp in Berthen, a few miles northwest of the British-held town of Bailleul, where German troops were attacking.

The next day, the 14th, Dr. Arnett was assigned to an advanced dressing station barely more than a mile from the fighting in Bailleul.

On the 15th, despite stiff British resistance, additional German attacks overran the town.

Dr. Arnett and his aides evacuated, returning to Berthen that evening.

Doctor John Deming Arnett was killed at Berthen the next day, April 16, when the camp was shelled while he was tending to the many wounded from the battles at Beilluel.

An article in the May 22, 1918 LeRoy Gazette-News relayed the details of his death as described by his mother-in-law, Mrs. Charles Sayers, in a letter to a friend in Pavilion. “Dr. Arnett was standing talking with three others, three miles back of the front line trenches, when a German shell exploded near them, a piece of it striking Dr. Arnett on the chest,” reads the article. “He lived ten minutes, but he did not speak.”

On April 10, 1918, six days before he was killed, Dr. Arnett wrote in a letter to Lula Pyatt, one of his patients in Pavilion:

“[I’m] Getting to be an experienced warrior now, but it is not a pleasant thing to get used to. The quietness of Pavilion would suit me better.”

The young doctor was buried the following day at a Trappist monastery atop Mont des Cats, a tree-covered ridge overlooking Berthen and the surrounding countryside.

After the war, Dr. Arnett’s remains were interred at Flanders Field American Cemetery in Waregem, Belgium, where his mother visited his grave in 1931 on a Gold Star Mothers Pilgrimage, and where he rests in peace and quiet today with 375 of his fellow Americans.

For source references and documents, and to read more information about Doctor Arnett’s life, see his Genesee County Honor Roll profile here.

Credits

Graduation photo courtesy of Albany Medical College Archives; Hospital of the Good Shepherd postcard retrieved from U.S. National Library of Medicine, Digital Collections (https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101459758-img); “Wounded British Soldiers Waiting,” © IWM, Imperial War Museum (http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205196017); “Ruins of Ypres,” National Archives Photo No. 165-BO-1702 (https://catalog.archives.gov/id/16581254); “British Soldiers Returning,” National Archives Photo No. 165-BO-1433 (https://catalog.archives.gov/id/16580716); “RAMC Stretcher Bearers,” © IWM, Imperial War Museum (http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205238026); “RAMC Advanced Dressing Station,” © IWM, Imperial War Museum (http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205196017); “Barricade at Bailleul,” National Archives Photo No. 165-BO-0751 (https://catalog.archives.gov/id/16579166); Arnett officer photo courtesy of the National Library of Medicine, History of Medicine Division (http://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/genealogy/amabiopage.html); Mrs. Virginia Arnett at grave photo courtesy of Millicent Arnett Matson.